The relationship between antibiotic use and cognitive decline in older adults has long been a topic of inquiry, shaped by concerns about the gut microbiome and its potential influence on brain health. A recent study examined this connection rigorously, yet it raised more questions than it answered, particularly regarding its implications for the broader elderly population. While the findings from this considerable research project seem reassuring, they demand careful scrutiny and context.

Conducted by Andrew Chan and his team at Harvard Medical School, the study followed 13,500 healthy older adults over approximately 4.7 years as part of the ASPREE trial, which primarily focused on the effects of aspirin among older populations. The researchers aimed to determine whether antibiotic use could be implicated in the long-term development of dementia or cognitive impairment. Their results indicated no significant correlation between antibiotic prescriptions and heightened risk of dementia, with hazard ratios suggesting negligible differences when comparing users and non-users. Additionally, antibiotic use was not linked to declines in cognitive function over time.

Despite these findings, caution is warranted. The study’s population was notably homogenous—predominantly white and healthier than the general older demographic—which limits the applicability of its results. It is important to recognize that while this research may alleviate some anxieties regarding antibiotic use in a specific healthy cohort, it is not indicative of all older individuals, particularly those with pre-existing health conditions or varying ethnic backgrounds.

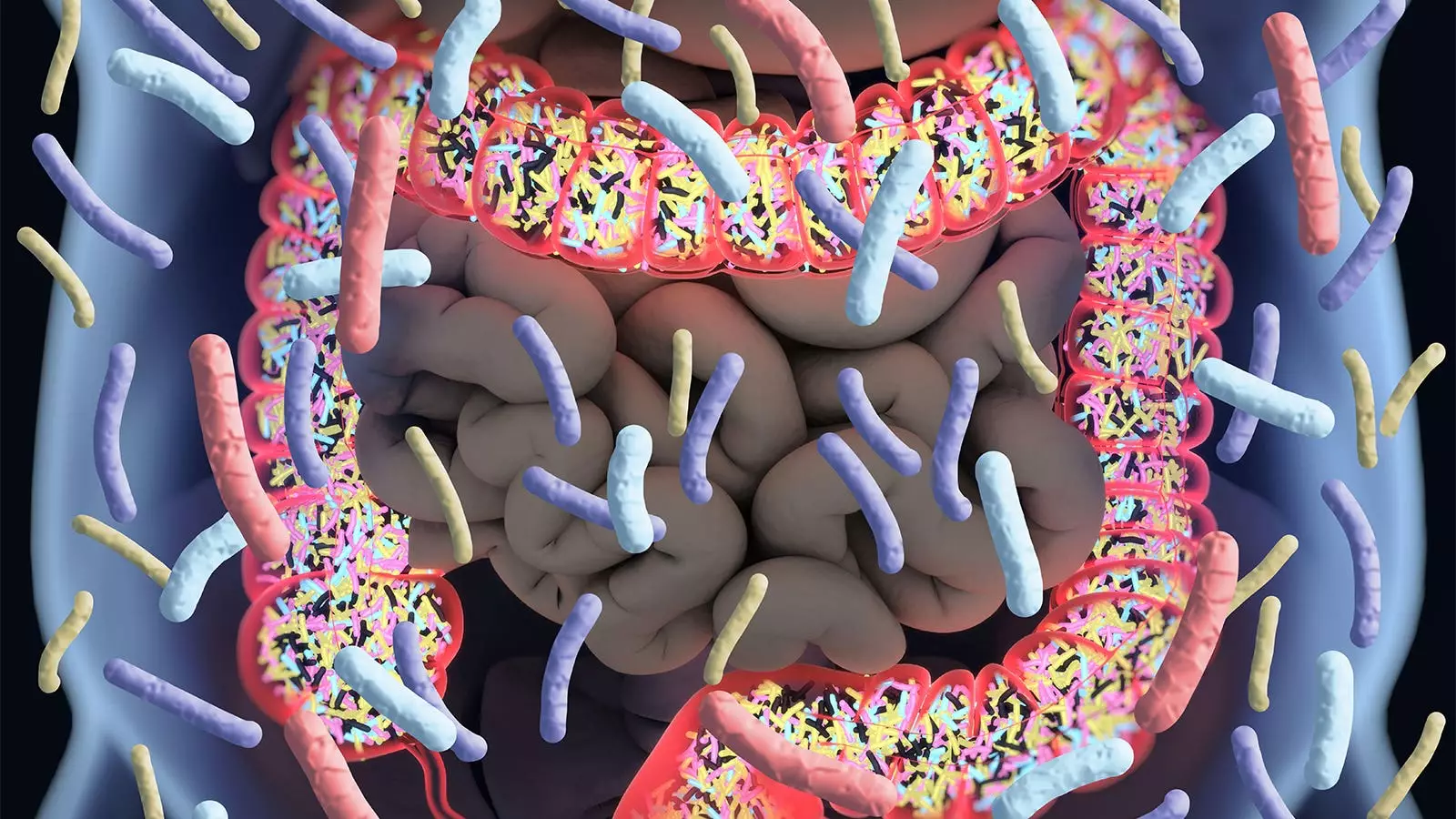

One of the critical factors in this study’s context is the role of the gut microbiome. Chan noted that antibiotics can cause significant disruption to gut flora, potentially affecting overall health and cognitive function. This ties into a broader narrative about the gut-brain axis, where disturbances in microbiome health might correlate with various neurological outcomes. Many previous studies have produced mixed results regarding the relationship between antibiotics and cognitive decline, leading to ongoing debates in the scientific community.

For instance, earlier investigations, such as the Nurses’ Health Study II, suggested that extensive antibiotic use in midlife could lead to subsequent cognitive deficits years later. This conflicting evidence emphasizes the complexity of understanding the long-term effects of antibiotic exposure on cognition. While the recent findings by Chan et al. present a more reassuring view for healthy, older adults, they also highlight the necessity of further research in diverse populations where gut microbiome dynamics may differ.

It is essential to approach the findings of the study with a critical lens, recognizing its inherent limitations. For instance, the reliance on filled prescriptions as a proxy for actual antibiotic use could introduce biases. Many patients may not take their prescribed antibiotics as intended, leading to inaccuracies in the data collected. Additionally, participants were primarily selected based on strict health criteria, raising concerns about residual confounding. These limitations underline the imperative for further studies that encompass a more diverse elderly population and consider varying health conditions.

In light of these discussions, the pursuit of rigorous clinical research remains paramount. Investigators should explore the cognitive consequences of antibiotic use across a spectrum of older adults, including those with chronic illnesses or differing ethnic backgrounds. Future research should also account for the varying classes of antibiotics and their specific impacts on cognitive health, as the present study did not find differentiated effects across commonly prescribed antibiotics.

While the findings from this study may offer a degree of reassurance to clinicians caring for healthy older patients, healthcare providers must resist overgeneralizing from this data. The careful interpretation of these results is critical for informed clinical decision-making. Despite the assurance given by the authors, medical professionals should remain vigilant regarding antibiotic prescriptions and strive to minimize unnecessary use, mindful of the potential disruptions to an individual’s gut microbiome.

Moreover, the inherent uncertainty surrounding the long-term impacts of antibiotics on cognitive health continues to warrant cautious prescribing practices. As antibiotics remain a cornerstone of modern medicine, understanding their complex relationship with cognitive function will require ongoing research and dialogue among clinicians, patients, and researchers alike.

The ongoing study of antibiotics and their implications for dementia risk in older adults reveals not only the need for rigorous scientific inquiry but also the importance of contextualizing findings within broader health issues. As researchers continue to unravel this complex web, both the medical community and the public will benefit from a more nuanced understanding of the implications of antibiotic use on cognitive health.

Leave a Reply